The Cloward Sign...cervical referral patterns

Ralph Bingham Cloward was an American Neurosurgeon born September 24th 1908 in Salt Lake City, Utah. He was a member of the Western Neurosurgical Society for 40 years and the President in 1975.

"Like many contributors to medicine, the [interbody fusion] technique was developed as a wartime necessity. Dr. Cloward was the only neurosurgeon in the Pacific when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. He was assigned by the army to remain in the Hawaiian Islands for the duration of World War II. The urgent need to build the island defences and the furious pace of hard work resulted in many low back injuries. Most of these were disc lesions causing incapacitating low back pain. A method of treatment was needed which would return the working man to his job in the shortest period of time. The interbody fusion after total disc removal was developed to meet this need." (Cloward Instruments, 2006).

In 1959 Dr Cloward published a landmark paper discussing the contribution of cervical intervertebral discs to neck pain. At this time it was accepted by medical physicians that neck pain can be caused by injury to the cervical ligaments or muscles, IVD disruption involving the adjacent nerve root, or cervical spondylosis. However, it remained difficult to isolate a particular anatomical structure as the single cause of neck pain. Dr Cloward (1959) used the technique of cervical diskography and open surgery to further explore the pain referral mechanisms of the IVD.

Physicians acknowledged that referred pain from IVD pathology was most likely due to encroachment/compression of the surrounding nerve root, however referred pain would often exist without radicular pain radiating down the upper limb or evidence of neurological compromise. It was with the results of this classic article (Cloward, 1959) that neurosurgeons and physicians discovered the pain referral patterns related to the IVD with/without nerve root involvement. These pain patterns were later described as Cloward Signs.

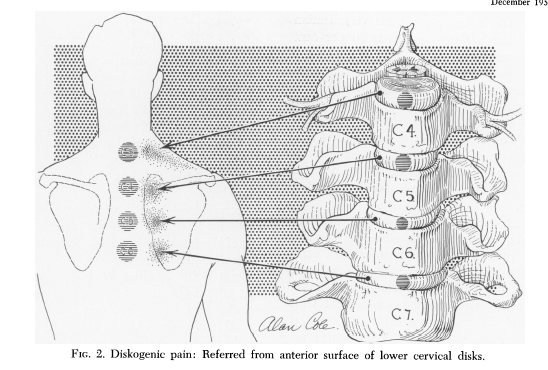

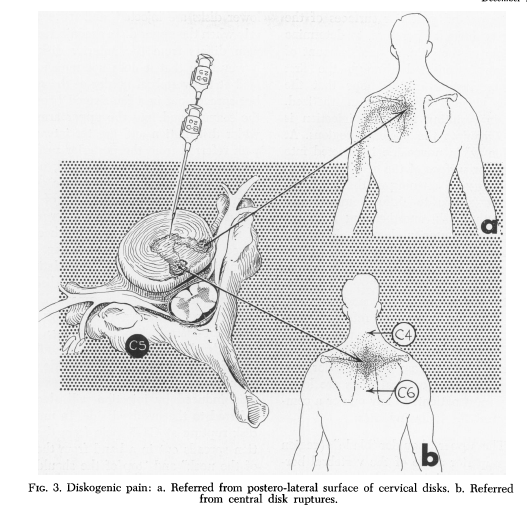

In this particular study (Cloward, 1959) they stimulated the anterior surface of cervical IVD on live patients, who then complained of severe pain around the ipsilateral scapular vertebral border (seen in the images below). Following needle stimulation of this region they applied a small amount of anaesthetic completely abolishing the pain. The authors found the anterior surface of IVD refers pain to the medial border of the scapula but doesn't produce upper limb symptoms. Stimulation of the posterior surface of IVD however may involve the upper shoulder blade, the base of the neck, the top of the shoulders, the point of the shoulder, and down the posterior arm stopping above the elbow (Cloward, 1959, p. 1057).

Other authors investigating this phenomenon found that muscle spasm in the area of referred pain is not due to local tissue pathology but an involuntary spasm secondary to the source of pain, known commonly by physiotherapists as secondary hyperalgesia and involuntary muscle spasm.

Cloward (1959) explained these pain referrals by exploring the clinical anatomy of the upper to mid thoracic spine. As we know, the skin in the region of the medial border of the scapula is innervated by T2-T7 spinal nerves. The muscles that lie in this region are innervated by the brachial plexus (C5-T1). Therefore local muscle dysfunction in the thoracic spine should always warrant an investigation of the contributing cervical spinal levels. In clinical practice this is achieved with assessment of cervical active and passive range of movements and assessment of passive intervertebral accessory and physiological movements (PAIVMS and PPIVMS).

So thats a small overview about the history of Dr Cloward and how we came to know that the IVD can refer pain even in isolation of nerve root involvement. His work provided us with these two illustrations (Cloward, 1959, p. 1056 & 1058 respectively).

Neck Pain

In the cervical spine the IVD and facet joints are innervated by the same spinal segment, making it difficult to determine whether both structures are implicated as the source of nociception, or, if one structure is sensitised through means of secondary hyperalgesia.

In the effort to identify which musculoskeletal structures (intervertebral disc, zygophophyseal joints, and muscles) are responsible for persistent neck pain, procedures such as cervical discography and zygopophyseal joint injections were developed. The procedure involves a provocation injection followed by an anaesthetic injection, to observe the change in neck pain symptoms. Abolishing of symptoms implicates the structure being examined.

A study by Bogduk & Aprill (1993) explored the nature of chronic neck pain using techniques mentioned above. The subjects of this study included people with a traumatic onset of neck pain for over six months duration. They revealed that many patients with neck pain will not have strong radiological evidence of structural pathology. 64% of the study participants were found to have positive neck pain signs with zygopophyseal joint and concurrent intervertebral joint procedures.

Although there are serious concerns about using cervical discography and zygophophyseal joint injections in isolation to other clinical examinations and investigations, it does question if patients without neurological signs or radicular upper limb pain warrant radiological or MRI investigation? Are there other examination procedures available to therapists to diagnoses these structures as a source of neck pain in the clinical setting without relying on medical imaging?

And I'm sure you are thinking YES. We do this every day.

In clinical practice, we rely more on clinical features and our manual examination of joint motion to reproduce our client’s neck pain, and to hypothesise which structure might be implicated. We use our knowledge of joint open and closing patterns, of IVD loading positions, aggravating and easing positions for each structure, and of the pain referral patterns to determine which structure is most likely responsible for the pain and therefore requires treatment.

Z-joint pain referral patterns

One study conducted by Bogduk (1996) identifies the pain referral patterns of cervical facet joints. This information was derived from 61 volunteers who underwent a zygopophyseal joint injection and facet joint denervation in a pain clinic in Japan.

They developed this referral chart for clinical use……

(Bogduk, 1996, p. 81).

There are also myofascial trigger points to consider. Have a look at some of the overlap which starts to occur in the following images.

Having done my masters in Musculoskeletal physiotherapy, I often place more emphasis on my assessment of the spine and joint mobilisation treatments. It is always useful to remember that primary myofascial trigger points exist within muscles and some patients may respond better to soft tissue treatment techniques than joint mobilisation. The treatment we choose is based on our clinical reasoning of the presenting patient. So remember to consider the clinical anatomy of the problem area and think about which spinal levels innervate that region, what lies beneath that region, and what lies above and below and could be referring to that region. Hopefully then, we choose the best region to apply our treatment.

Myofascial trigger points and referred pain patterns (courtesy of Google images).

Clinical case examples.

Patient 1:

A middle aged women presented with severe stabbing pain along the line of her ribs in the middle of her left chest. This pain was intense and stopping her from breathing and almost all movement. In the waiting room she sat with her neck rotated to the left and flexed down and holding her left arm into her chest, an antalgic posture I'm sure we've all seen.

Subjectively there was no MOI and no report of neck pain. She just felt she couldn't breathe. But her instinctive neck positioning led me to ask about her neck and it turned out the day prior she had been on a roller coaster and although painfree at the time, woke the next morning with this pain.

On physical examination she was unable to correct her neck position without excruciating chest pain and my assessment was severely limited. I suspected a low cervical discogenic wry neck based on the cloward signs and her antalgic position. My management was to send her home with a soft collar (which immediately reduced her chest pain), rest for one-two days and take analgesics/NSAIDS as required.

She returned day 2 (2 days later) with 50% of her neck movement restored and minimal pain in her chest. She was still cradling her arm though and therefore limited in ADL's. Day 2 management involved cervical mechanical traction of 6kg for 10 minutes and scapula taping to elevate and offload her neck/shoulder.

By day 3 (one week) she had full cervical range of movement, full shoulder function and only reproduction of symptoms with PAIVMS. Day 3 treatment involved cervical mobilisations over the C6/7 articular pillar (being careful to use a Gr III- pressure), cervical AROM into rotation and lateral flexion. There was no Day 4 as the patient had made a full recovery.

On reflection I needed to change my treatment plan every session to adjust to the rapid improvement being made. The reason I chose this case is because the initial assessment was so limited that I had to use my knowledge of pain referral patterns and antalgic postures to make an educated guess without any other physical tests or objective signs. Rarely do I go for the soft collar as a treatment, but in this case it offloaded the pain sensitised structures enough to allow for further assessment/treatment.

Patient 2:

A female in her early 30's presents with pain and tightness in her right medial border of her scapula (which she described as her rhomboids). Again an unknown MOI or nothing significant that correlates with the onset of symptoms. She had been seen by another physiotherapist who assessed her problem and chose to treat her rhomboid tightness with cupping and deep tissue massage.

There were big bruises on her back indicating where the treatment took place. I showed this patient the picture above of Cloward's referral patterns, from his study in 1959... and they were a perfect match.

On physical examination there was no loss of thoracic range of movement. Cervical flexion, extension and retraction were very painful and increased her 'rhomboid' pain. Downward spinal compression again increased her pain, confirming for me that the cervical spine was implicated as a source of pain. On palpation her medial scapula pain was reproduced with central PA of C4.

I managed this patient with gentle rotation AROM and retraction as a HEP, manual cervical traction Day 1, rest from the gym, analgesics/NSAIDs as required, and scapula taping. She felt this was a very conservative approach compared to the previous therapist, and it is. Sometimes treatment focuses on allowing the pain sensitised structure to settle and then assessing further to determine what treatment is required. In this case she settled in 2 days and didn't require much mobilisation/treatment to restore her full cervical range of movement.

These are two examples where patients presented with somatic referred pain from the cervical spine, with no primary neck pain, no upper limb symptoms and no signs of neurological compromise. Both settled quickly with appropriate rest, NSAIDS and treatment techniques targeted at reducing pressure on the pain sensitive structures and to promote normal and healthy movement in the cervical spine.

Although the research discussed today was done many years ago, the finding of the studies has led to the development of an invaluable mapping of pain referral patterns. In particular, the recognition of a “Cloward Sign” is a clinical tool I was given after graduating university and I find it true clinical gem, which I wish to pass on to you.

Sian

References

Aprill, C., & Bogduk, N. (1992). The Prevalence of Cervical Zygapophyseal Joint Pain; A First Approximation. Spine, 17(7), 744-747.

Bogduk, N., & Aprill, C. (1993). On the nature of neck pain, discography and cervical zygapophysial joint blocks. Pain, 54(2), 213-217.

BOGDUK, N., WINDSOR, M., & INGLIS, A. (1988). The innervation of the cervical intervertebral discs. Spine, 13(1), 2-8.

Cloward Instruments (2006). http://cloward.com/pg_about.html

Cloward, R. B. (1959). Cervical diskography: a contribution to the etiology and mechanism of neck, shoulder and arm pain. Annals of Surgery, 150(6), 1052.

Roth, D. A. (1976). Cervical analgesic discography: a new test for the definitive diagnosis of the painful-disk syndrome. Jama, 235(16), 1713-1714.

Wainner, R. S., Fritz, J. M., Irrgang, J. J., Boninger, M. L., Delitto, A., & Allison, S. (2003). Reliability and diagnostic accuracy of the clinical examination and patient self-report measures for cervical radiculopathy. Spine, 28(1), 52-62.

Western Neurosurgical Society (2014). http://www.westnsurg.org/clowardaward.asp