Temporomandibular Joint Disorders - Clinical Anatomy & Assessment

"The sound of loud crashing waves in my ear."

Recently a patient presented with a severe headache, neck stiffness and a sudden onset of "the sound of loud crashing waves in my ear", which was so loud it interrupted her concentration, sleep and was making her feel very sick.

When questioning about the aggravating factors this patient said "sitting at the computer, lying down to sleep, and eating a toasted sandwich", but nothing eased the noise.

She had seen her GP, who referred her to an audiologist and the outcome of her assessment was perfect hearing and no sign of an ear infection. She was a young & healthy female who had a history of cervicogenic headaches which commenced following the removal of her wisdom teeth in 2013. With this presentation her headaches were similar to past headaches, however, this noise was an unusual descriptor. This, in combination with her wisdom teeth being removed, made me consider that the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) might be involved.

This particular case has prompted me to write about TMJ disorders (TMD) and their connection to OR differentiation from upper cervical joint dysfunctions and headaches.

The aim of this blog is to review the clinical anatomy, biomechanics and assessment of TMJ disorders. There will be a second blog which outlines the current evidence-based treatment techniques and a overview of how I managed this patient.

Anatomy

The Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is a synovial joint, which is formed by the articulation of the condyle of the mandible and the mandibular fossa of the zygomatic arch.

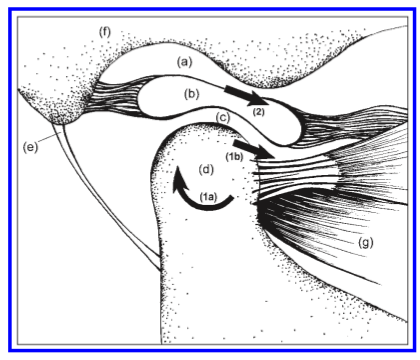

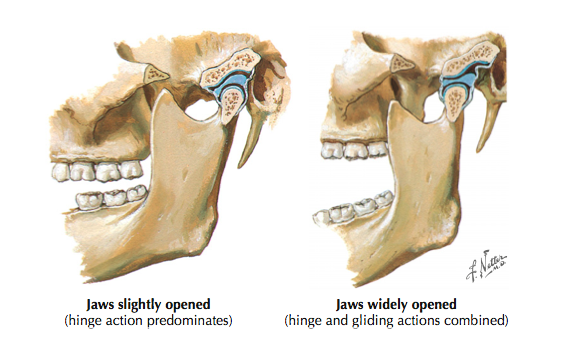

There is an biconcave articular disc which separates the joint into two functional compartments. The top joint (disco-temporal) is a plain-gliding joint which permits translation and the bottom compartment (disco-mandibular) forms a hinge joint that permits rotation movements. This enables the mandibular condyle to roll and slide on the fossa above (Shaffer, Brismée, Sizer, & Courtney, 2014). The articular disc attaches anteriorly to the joint capsule and posteriorly to the retrodiscal ligament which allows for disc and bone to move together.

"The articular surfaces of the TMJ are highly incongruent and consist of fibrocartilage, not hyaline cartilage like other synovial joints. The TMJ is subject to degenerative changes, though the temporal bone and upper joint space generally undergo less degeneration relative to the mandibular condyle and lower joint space" (Shaffer, Brismée, Sizer & Courtney, 2014, p.3).

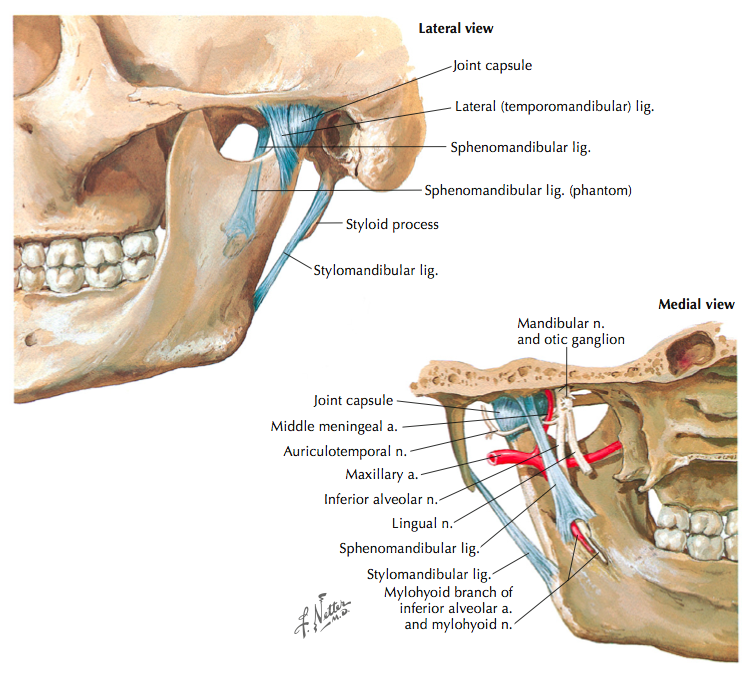

Ligaments:

- The joint capsule is fairly loose allowing for large degrees of movement. "The capsular pattern of the TMJ has been reported as opening, protrusion, and lateral deviation" (Shaffer, Brismée, Sizer & Courtney, 2014, p.3).

- Retrodiscal ligament (not shown here) which attaches to the posterior margins of the articular disc.

- Temporomandibular ligament is a thickening of the anterior joint capsule that strengthens the TMJ laterally.

- Sphenomandibular ligament which extends from the sphenoid bone to mandible and reinforces the joint and acts as a fulcrum to rotation.

- Stylomandibular ligament which extends from the styloid bone to angle of mandible, but doesn’t give much stability to the joint.

(Cleland & Koppenhaver, 2007. p.21)

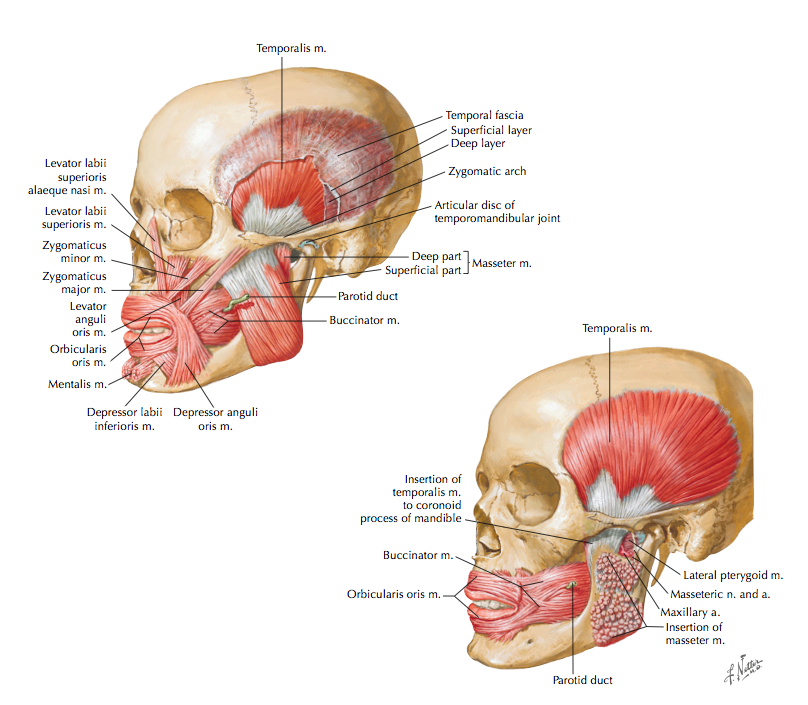

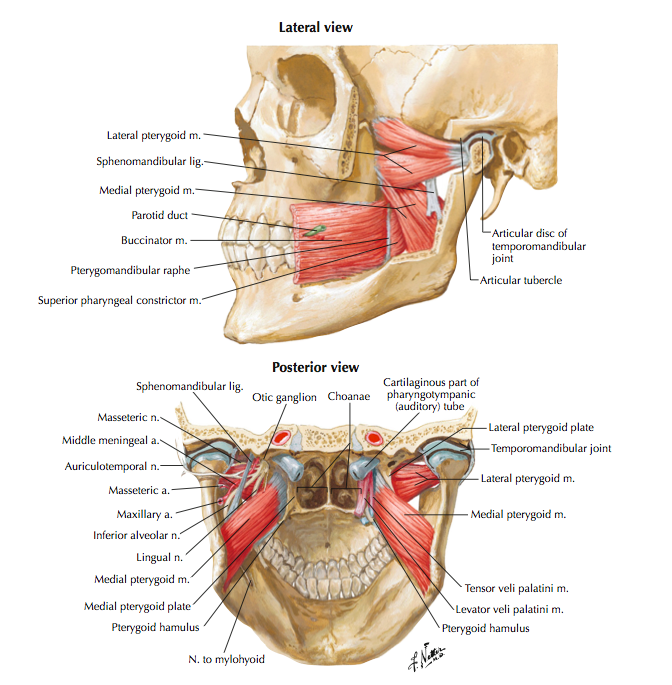

Muscles around the TMJ:

- Muscles of mastication (innervated by CN V trigeminal nerve)

- Closers:

- Temporalis – elevates mandible

- Masseter – elevates and protrudes mandible

- Medial pterygoid – elevates and protrudes mandible

- Openers:

- Lateral pterygoid – acting bilaterally to protrude and depress mandible, acting unilaterally to laterally deviate mandible

- Closers:

- Accessory muscles consisting of the suprahyoid and infrahyoid muscles (don't provide much stability around the TMJ).

- Geniohyoid, mylohyoid, and digastric – assist with depression of the mandible and elevate hyoid bone.

(Cleland & Koppenhaver, 2007: Shaffer, Brismée, Sizer & Courtney, 2014):

"Importantly, despite the fact that clenching and bruxism (teeth grinding) are frequently associated with TMD and TMD-based myalgia, no significant difference in EMG readings has been noted between patients with TMD and control groups" (Shaffer, Brismée, Sizer & Courtney, 2014, p.3). Which means that although bruxism (clenching) is a common finding it might not be a causative factor in TMD.

(Cleland & Koppenhaver, 2007. p.22)

(Cleland & Koppenhaver, 2007. p.23)

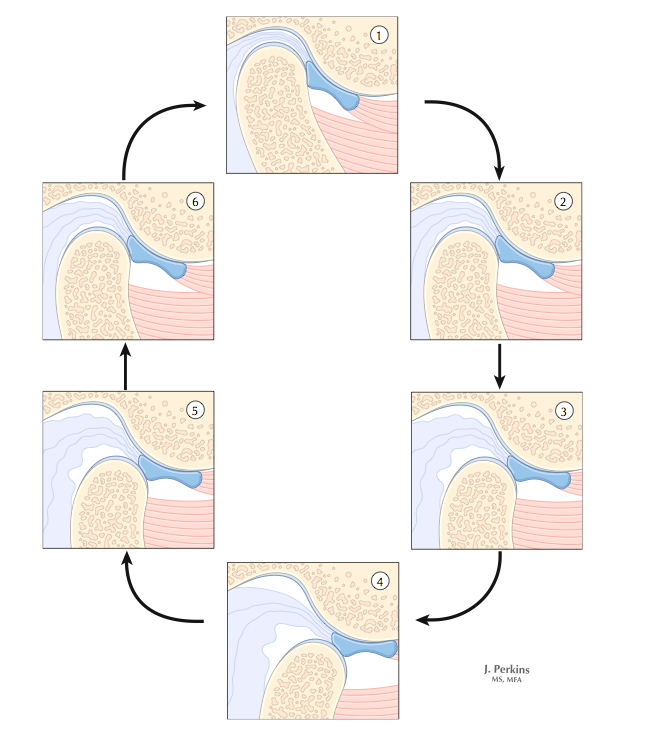

Athrokinematics of the TMJ during opening (Shaffer, Brismée, Sizer & Courtney, 2014, p.4)

TMJ biomechanics

The closed pack position is full occlusion and the capsular pattern is full opening.

During opening movements (depression of the mandible) there is approximately 40-50mm of movement. The first 11mm of depression are isolated to the lower joint and after that a combination of anterior translation of the upper joint and rotation of the lower joint occurs. During closing the first movement comes from the upper joint and sliding of the disc, and the lower joint movement occurs later in the closing movements. It is always a combination of sliding, rolling and hinging movements.

"Condylar head movement during lateral deviation has been described as ipsilateral lateral rotation (spinning) with contralateral anterior translation and medial rotation" (Shaffer, Brismée, Sizer & Courtney, 2014, p.4).

Protrusion is achieved with bilateral anterior translation of the mandibular condyles.

Movements of TMJ involve:

- Physiological movements = depression, elevation, protrusion, retraction and laterally deviation.

- Accessory movements = anteroposterior, transverse and caudad/cephalad movements.

'There is considerable debate wether malocclusion is a causative factor for TMD' (Selvaratnum, et al., 2009). None-the-less, the occlusal position is still an important part to watch during opening and closing of the mouth (Maitland, 1991, p. 293).

(Cleland & Koppenhaver, 2007. p.20)

TMJ assessment

"The Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (RDC/TMD) was developed in response to a general lack of standardisation in TMD assessment and diagnosis. The RDC/TMD is based on a biopsychosocial model and is comprised of a comprehensive set of history questions and physical examination procedures. The examination includes measurement of the range of mandibular motion, muscle and joint palpation with defined pressure, and recording of joint sounds. The specific examination questions, procedures, and scoring instructions are available at a website created by a consortium of worldwide researchers using the RDC/TMD" (Cleland & Koppenhaver, 2007. p.31).

The RDC/TMD is more extensive than I could achieve in the clinical setting so the assessment outlined below is an overview of my clinical practice. I have drawn on information from the RDC/TMJ, Cleland's anatomy text, and the experience of colleagues and clinical supervisors.

Subjective assessment:

- Aside from the normal format of a subjective assessment the following question areas are more tailored to the TMJ. Remember to question about the patient's dental health and daily habits e.g. sleeping habits, chewing habits, clenching, braces, and wisdom teeth.

- Symptoms:

- Pain can be reported around the TMJ, along the line of the jaw, in the muscles of the jaw and temple (masseter and temporalis), and the upper cervical spine (both anteriorly near the origin of SCM and posteriorly around the suboccipital region).

- Note the quality, severity, behaviour of the pain or other symptoms.

- A fullness in the ear, pulsating in the ear, and ringing/tinitus might be more related to an inner ear pathology, peripheral vestibular dysfunction (Meniere's disease) or carotid artery dysfunction.

- Pain can be reported around the TMJ, along the line of the jaw, in the muscles of the jaw and temple (masseter and temporalis), and the upper cervical spine (both anteriorly near the origin of SCM and posteriorly around the suboccipital region).

- Aggravating activities:

- It is important to ask what activities provoke their jaw pain, or what activities are limited by their jaw pain e.g. biting into apples, chewing a sandwich, or eating steak.

- Chewing, drinking, exercising, eating hard foods, eating soft foods, smiling/laughing, sexual activity, cleaning teeth or face, yawning, swallowing, talking, having your usual facial appearance are all aggravating activities involved in the Jaw Dysfunction Questionnaire.

- Clicking sounds during movements may include:

Clicking or crepitus during opening/closing.

Joint sounds during lateral excursion (contralateral side/ ipsilateral side) or during protrusion.

These noises may also resonate along the bone and be heard within the ear.

- Locking vs Restricted movements.

- Does this occur during opening or closing movements?

- Does it occur after a clicking sensation?

- How long does it take to ease and what eases it?

- Is this restriction periodic (if so, how often does it occur) or continuous?

- Use of occlusal splints or other corrective splints.

- Headaches

- Although headaches are a symptom often reported with TMD, there remains a lack of high-quality evidence to support that all headaches experienced with TMD are related to the TMJ. Those studies which do identify headache symptoms arising from the TMJ and surrounding structures describe the headache as a unilateral headache in the "pre-auricular region, temple and retro-orbital regions of the head" (Zito, Morris & Salvaratnum, 2008, p. 331).

- Subjectively symptoms are felt over the temple, ear, and along the jaw line. Sometimes they radiate to the neck.

- The pain referral can be anywhere along the pathway of the trigeminal nerve.

- Headaches can be both bilateral and unilateral depending if one/both of the TMJs are affected.

- Twice as common in females than males, present in ages from 19-83 (wide age bracket).

- There is no clear pattern on behaviour i.e. one can wake with pain or develop it during the day and the headache may be intermittent or continuous. (Zito, Chapter 8, Headaches, Orofascial pain and Bruxism, 2009, p. 83).

- On physical examination it is important to evaluate the effect of head posture, jaw mobility muscle dysfunction, on the headache and its relationship to other symptoms reported by the patient (Zito, Chapter 8, Headaches, Orofascial pain and Bruxism, 2009, p. 83).

- Remember that pain felt in these regions is not specific to TMD and are reported in primary headaches such as migraines and tension-type headaches, as well as other secondary headaches such as cervicogenic headaches (Selvaratnum, et al., 2009, p. 78).

- Differential diagnosis and classification of headaches is a topic for a separate blog, but if you are interested in reading further I would recommend the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD, 2004).

- Red Flags:

- " History of emotional or psychological stress, medication usage, symptoms of vertebrobasilar insufficiency, upper cervical spine instability, cardiac dysfunction, central nervous system dysfunction, cranial nerve dysfunction, infection, and unexpected weight loss or gain" (Shaffer, Brismée, Sizer & Courtney, 2014, p.6).

Physical Examination:

- Occlusal position

- Observation of posture of the jaw, head, neck and thorax. (You will read further in the treatment blog that posture plays a big role in jaw movement retraining.)

- Mandibular range of movement:

- Active movements

Unassisted opening without pain - should be > 5cm as the mean or > 3 fingers width. Limited opening < 25mm between top and bottom jaw.

Maximum unassisted opening

Maximum assisted opening

Lateral excursions - watch the movement of the bottom molars which should move ~1cm to each side.

Protrusion - if the bottom teeth move forward of the top teeth 2-3cm, or 1-2 fingers, then the movement is considered functional.

Measuring AROM can be done in many different ways using tools. I use visual observation for lateral deviation and protrusion, and the number of fingers between top and bottom jaw for opening. Each of my fingers is 1.5 cm wide - measure yours to use them as an assessment tool.

- Passive physiological movements are done by the therapist and requires you to place one thumb inside the bottom jaw.

- Passive accessory movements over the internal TMJ can be done with the fifth digit at the same time as internal palpation.

- Active movements

- Palpation

- Internally:

- Medial pterygoid, internal TMJ and gums.

- Externally:

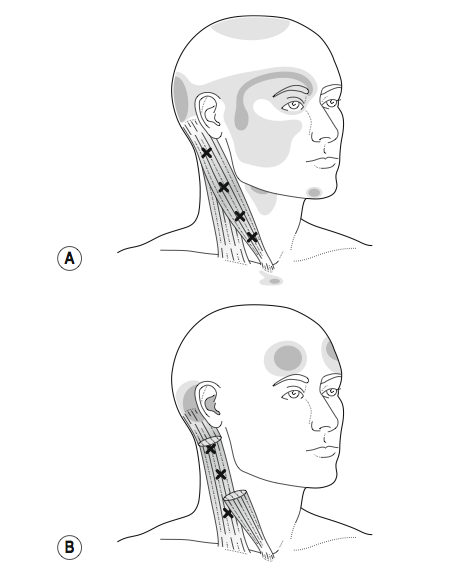

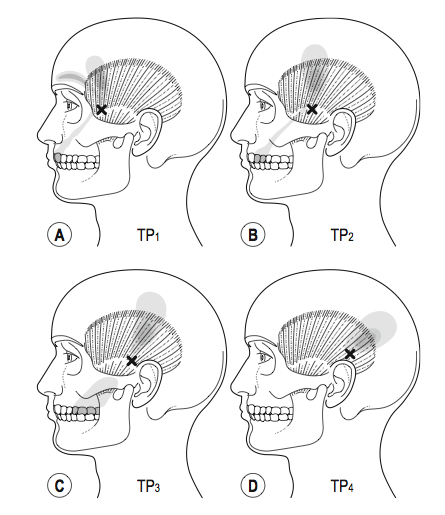

- Masseter, temporalis, lateral pterygoid, TMJ, C1 t.p, and SCM proximal muscle belly.

- Internally:

- Isometric strength tests of mandibular elevation, depression, lateral deviation and protrusion.

For further detail on the physical examination, I would recommend the part 1 article by Shaffer, Brismée, Sizer & Courtney (2014) which discusses each technique in detail with regards to therapist positioning, palpation technique and how this can be transferred into a treatment.

Once the assessment is completed, the next step is to diagnose the type of TMJ disorder as they are a heterogenous group of disorders.

The research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (RDC/TMD) was revised and published in 2010 and is used by researches for subgrouping TMJ disorders into five main subgroups. These are:

- Myogenic

- May present with or without limited mouth opening.

- Often associated with bruxism.

- Often confirmed with palpation of muscles reproducing pain referrals and response to soft tissue treatment techniques.

- Arthrogenic

- Associated with joint pathology i.e arthropathy, athralgia, hypermobility.

- Presence with audible/palpable crepitus.

- Assessment of joint compression and passive/active movement dysfunction and confirmed from response to joint manual therapy treatments.

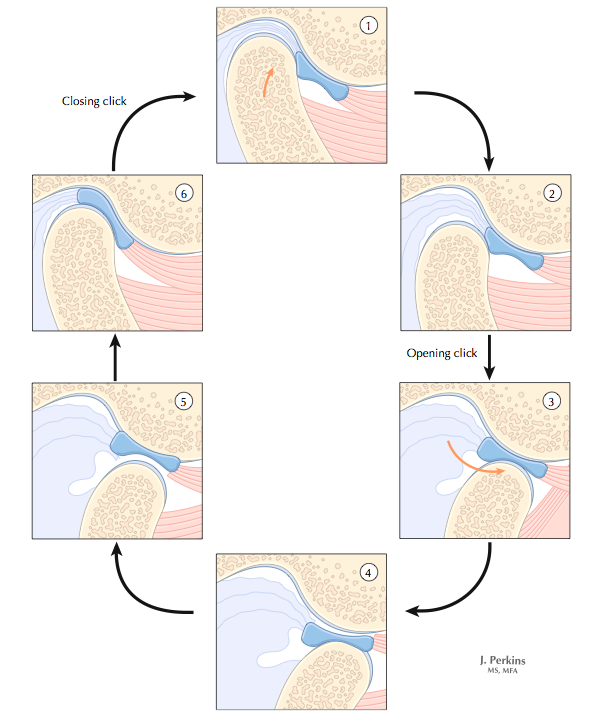

- Disc displacement with reduction

- Associated with joint noises but not locking.

- Can be painful or painfree.

- "A disc displacement with reduction is associated with altered position of the disc in its relationship to the mandibular condyle in the closed mouth position that relocates with a clicking sound (<35mm) when the mouth is opened" (Selvaratnum, et al., 2009, p. 73).

- Disc displacement without reduction.

- May present with or without limited mouth opening which in the acute phases is often painful.

- Cervical spine involvement.

- Often concurrent with TMD with dysfunction found on accessory movement examination, cervical palpation and confirmed with response to manual therapy.

Somatic referral mapping of sternocleidomastoid (Selvaratnum, et al., 2009, Headaches, Orofascial Pain, and Bruxism. Elsevier, p. 72).

Somatic referral mapping of masseter (Selvaratnum, et al., 2009, Headaches, Orofascial Pain, and Bruxism. Elsevier, p. 72).

Disc displacement with reduction during opening (Cleland & Koppenhaver, 2007. p.54)

Disc displacement without reduction during opening (Cleland & Koppenhaver, 2007. p.56)

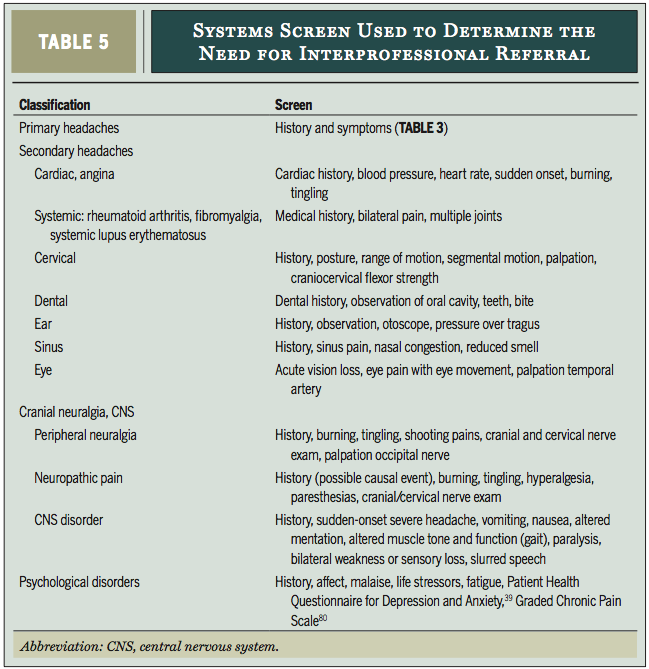

Differential diagnosis

It can be difficult to differentiate between symptoms arising from the cervical spine, TMJ and ear given the proximity of each region and their capacity for pain referral through a nociceptive pain mechanism with a somatic referral. Here are just a few things to keep in mind...

Cervicogenic headaches

"There are several reasons why the diagnostic process is so difficult. The close neuroanatomical and biomechanical connections between the cervical and temporomandibular regions makes the headaches arising from the two areas similar and difficult to distinguish" (Zito, Chapter 8, Headaches, Orofascial pain and Bruxism, 2009, p. 83).

"Cervical facet joints and upper cervical neuronal structures can cause orofacial pain. Cervical spine disorders may exacerbate TMDs as a result of the convergence of sensory information from the cervical spine influencing the trigeminal nucleus at the spinal cord level" (Harrison, Thorp & Ritzline, 2014, p. 188).

Currently three musculoskeletal impairments have been validated as clinical features of CGH: a painful upper cervical joint, loss of range of movement, and impairment in the muscular system of the cervical spine (Jull, Amiri, Bullock-Saxton, Darnell, & Lander, 2007: Kind, Lau, Lees, & Bogduk, 2007:, Zito, et al., 2006). These clinical findings have been validated to "delineate people with cervicogenic HAs from those with primary HAs with 100% sensitivity and 90% specificity" (Harrison, Thorp & Ritzline, 2014, p. 188).

Ear infection

"Ear disorders, such as an inner or outer ear infection, can produce pre-auricular symptoms in and around the TMJ. Conversely, hyperactivity of the masticatory and tensor tympani muscles can cause ear pain, tinnitus, and feelings of fullness in the ear" (Harrison, Thorp & Ritzline, 2014, p. 189).

Temporal arteritis

Temporal arteritis aka 'giant cell arteritis' is a vascular disorder (vasculitis) which presents clinically with a headache in the region of the temples (just above the TMJ). I've chosen to describe this condition a bit further because it isn't highlighted in the table below. Other symptoms of temporal arteritis may include fever, malaise, jaw pain, pain with chewing, loss of appetite, pain and stiffness in the neck and shoulder, tenderness on palpation, sensitivity over the scalp, blurred vision, double vision, and diplopia. Many of these symptoms are recognised by physiotherapists as red flags. According to Hunder and colleagues (1990) temporal arteritis can be diagnosed with sensitivity of 93.5% and specificity of 91.2% if patients score 3/5 of the following 5 questions:

Age over 50 years

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) > 50 mm 1st hour

Superficial temporal artery tenderness

Temporal headache

Positive histology of a temporal artery biopsy (Unilateral biopsy of a 1.5–3 cm length is 85-90% sensitive).

Below is a table which outlines the symptoms which patients may report which are now related to TMJ disorders and require medical follow-up. The main differentiating symptom to TMD is the relationship to activities using the jaw i.e. symptoms with yawning, eating, chewing etc.

Differential diagnosis of TMJ (Harrison, Thorp & Ritzline, 2014, p. 190).

Radiological findings

MRI is the best imaging to show both the TMJ and the disc. A normal disc will appear the same on both T1 and T2 weighted images. The will be an increased signal intensity on T1 images with acute disc derangement. MRI images should be taken with the mouth open and closed to visualise the movement of the TMJ and intra-articular disc (Lee & Yoon, 2009). The disc is difficult to see on CBCT which is why MRI is the recommended imaging.

This blog is a bit longer than I originally hoped but only because there is so much great information available and it can be a tricky region of the body to treat. My hope is that you found it worthwhile to stick it out to the end. The next blog will review the treatment techniques available for TMJ disorders.

Sian :)

Bibliography

Al Ani, M. Z., Davies, S. J., Gray, R. J. M., Sloam, P., & Glenny, A. M. (2009). Stabilisation splint therapy for temporomandibular pain dysfunction syndrome. The Cochrane Library(1).

Cleland, J., & Koppenhaver, S. (2007). Orthopaedic clinical examination : an evidence-based approach for physical therapists (2nd ed.): Elsevier.

Harrison, A. L., Thorp, J. N., & Ritzline, P. D. (2014). A Proposed Diagnostic Classification of Patients With Temporomandibular Disorders: Implications for Physical Therapists. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy, 44(3), 182-197.

Hunder, G. G., Bloch, D. A., Michel, B. A., Stevens, M. B., Arend, W. P., Calabrese, L. H., ... & Zvaifler, N. J. (1990). The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of giant cell arteritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 33(8), 1122-1128.

Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. (2004). The international classification of headache disorders. Cephalalgia: an international journal of headache, 24, 9.

Jull, G., Amiri, M., Bullock‐Saxton, J., Darnell, R., & Lander, C. (2007). Cervical musculoskeletal impairment in frequent intermittent headache. Part 1: Subjects with single headaches. Cephalalgia, 27(7), 793-802.

Kirk, W. S., Jr., & Calabrese, D. K. (1989). Clinical evaluation of physical therapy in the management of internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery, 47(2), 113-119.

King, W., Lau, P., Lees, R., & Bogduk, N. (2007). The validity of manual examination in assessing patients with neck pain. The Spine Journal, 7(1), 22-26.

La Touche, R., Paris-Alemany, A., von Piekartz, H., Mannheimer, J. S., Fernandez-Carnero, J., & Rocabado, M. (2011). The influence of cranio-cervical posture on maximal mouth opening and pressure pain threshold in patients with myofascial temporomandibular pain disorders. The Clinical journal of pain, 27(1), 48-55.

Lee, S. H., & Yoon, H. J. (2009). The relationship between MRI findings and the relative signal intensity of retrodiscal tissue in patients with temporomandibular joint disorders. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology, 107(1), 113-115.

Maitland, G. D. (1991). Peripheral manipulation (3rd ed.). London ; Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Selvaratnam, P., Niere, K. R., & Zuluaga, M. (2009). Chapter Seven & Eight. Headache, Orofacial Pain and Bruxism. P. Churchill, Livingstone, Elsevier. 69-82.

Shaffer, S. M., Brismée, J. M., Sizer, P. S., & Courtney, C. A. (2014). Temporomandibular disorders. Part 1: anatomy and examination/diagnosis.Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy, 22(1), 2-12.

Zito, G., Jull, G., & Story, I. (2006). Clinical tests of musculoskeletal dysfunction in the diagnosis of cervicogenic headache. Manual therapy, 11(2), 118-129.

Zito, G., Morris, M. E., & Selvaratnam, P. (2008). Characteristics of TMD headache–a systematic review. Physical Therapy Reviews, 13(5), 324-332.

Zito. (2009). Chapter 8. Headaches, Orofascial Pain and Bruxism. Churchill, Livingstone, Elsevier. 83-99.