Defining Clinical pilates exercises and its indications for treatment

Pilates exercises

"Pilates exercise is a mind-body intervention that focuses on strength, core stability, flexibility, muscle control, posture and breathing" (Wells, Kolt, Marshall & Bialocerkowski, 2013, p. 2).

"Despite its popularity, the effectiveness of Pilates exercise in people with CLBP is debated in the literature" (Wells, Kolt, Marshall & Bialocerkowski, 2014, p. 807).

These quotes describe two themes:

- What pilates exercise is, and

- What is the treatment effect for lower back pain when compared to other forms of general exercise?

There are many methodological reasons which explain the debate in the literature with regards to its effectiveness. These include the lack of heterogenity of LBP, inconsistency in patient assessment, inconsistency in prescription of exercises, degrees of supervision, and use of equipment, between studies. This blog is not a systematic review on the current evidence to support the use of pilates exercises (that's a topic for a separate discussion). Instead it is a discussion about the definition and application of pilates exercise and the indications, benefits and risks of this approach.

Even though the research debates its clinical efficacy in the treatment of lower back pain, we still use it. Melbourne is a hub for pilates and most physiotherapists have been trained in some form of the pilates approach.

Wells and colleagues published two articles in 2013 and 2014 which have caught my attention. Both use a delphi-study method (with Australian Physiotherapists who teach pilates and were trained through DMA or Polestar) to develop consensus about the definition and application of pilates exercise and the indications, benefits and risks of this approach.

And it got me thinking.... when I assess a patient to join our clinical pilates program, do I make a judgement on whether they are likely to benefit from this treatment approach? Do I thoroughly assess the contraindications and precautions for enrolment in our program? And when patients ask about our program, can I provide them with a clear description of what clinical pilates is and how it applies to their treatment plan? I do formulate thoughts about these questions but it was not until I read these articles that I realised the undeniable variability that exists between each therapist who teaches the clinical pilates approach and how this might impact on the benefits a patient will get from this form of exercise.

Who is likely to benefit and what are the indications for pilates exercise?

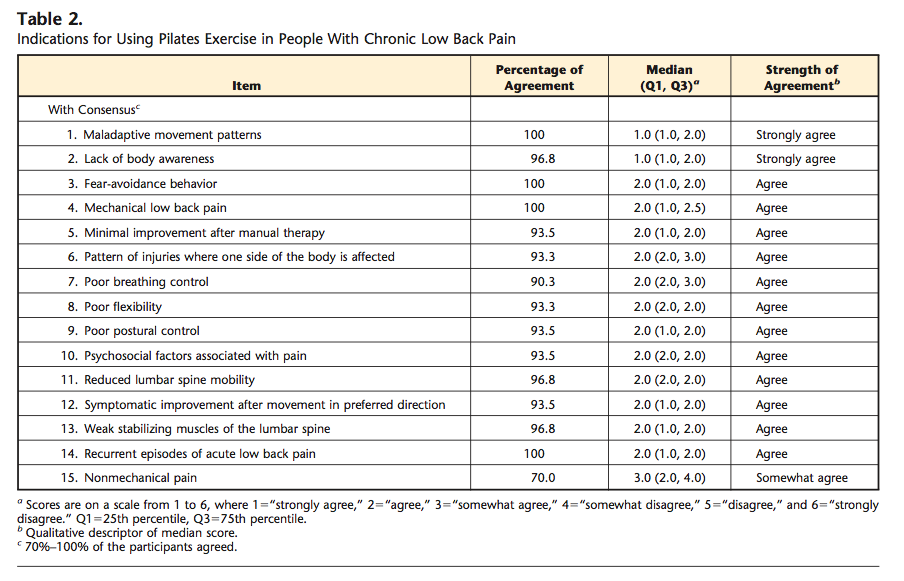

When considering the indications for pilates exercise and the results of this study, there was 100% consensus that those who lacked body awareness and displayed maladaptive movement patterns would benefit from pilates exercise (Wells et al, 2014, p.809). There was also consensus that non-mechanical pain is not an indicator for pilates exercise.

There were many other indications that didn't reach the same degree of consensus but are still worth considering...

Indications for using pilates exercise in people with chronic lower back pain (Wells, Kolt, Marshall & Bialocerkowski, 2014, p. 810).

There was 100% consensus with strong agreement that the benefits of pilates include

- Increased flexibility.

- Increased confidence with movement and aggravating activities.

- Increased body awareness.

- Increased postural control.

- Provision of adjustable resistance with exercise equipment.

There is fairly strong agreement that pilates may: reduce fear avoidance behaviours, unhelpful attitudes and beliefs about pain, reduce severity of exacerbations, enhance client understanding of their condition, enhance mind-body connection, provide relaxation, encourage normal breathing patterns, increase socialisation and participation, reduce pain severity and recurrence, increase spine stabilising muscle activity, and increase muscle strength.

Currently there are no research trials which evaluate the above benefits, with most trials evaluating treatment effectiveness based on pain severity reduction, disability reduction, functional improvement and in some cases rate of return-to-work. Therefore there may be a discrepancy in the reasons we choose clinical pilates as a treatment and our expectations of the benefits for the patients, and the outcome measures which research trials use to measure effectiveness.

It can also be argued that these benefits can be said for many other forms of exercise and they are yet to be proven as individualised benefits of pilates exercise and yet to be investigated as long term benefits.

What are the contraindications, precautions and risks of this approach?

Overall agreement on contraindications occurred for only 55% of the suggested themes. Two conditions reached strong agreement as contraindications, which were pre-eclampsia and unstable fractures. Both of these conditions are well supported in the literature as contraindications to exercise.

Other contraindications which reached >80% consensus were: acute pain, severe night pain, possible fracture, possible tumour, abdominal hernia, and possible infection. These are also relative contraindications for other treatment forms such as manual therapy and dry needling.

It raises the questions that if they are not absolute contraindications (i.e they are not validated by the literature) should we still seek medical clearance for medical conditions that are not necessarily associated with the patients back pain or primary problem?

There are also many conditions to be viewed as precautions to pilates exercise.

Precautions of pilates exercise for people with chronic low back pain (Wells, Kolt, Marshall & Bialocerkowski, 2014, p. 812).

With all treatments there are associated risks and the same goes for pilates exercises. In this study only 50% of the suggested risks associated with pilates exercises were agreed on, which included increased lower back pain and aggravation of the condition.

There was some agreement on risks such as: falling, not improving, causing injury, becoming anxious, becoming hypervigilant, and developing excessive muscle tone.

Other risks not agreed on but which relate to the practitioner include: not addressing poor concentration of client, poor instruction, poor client education, poor exercise supervision, inappropriate exercise prescription, too rapid progression, excessive load, overemphasis on core muscle activation, over emphasis on pain over function, and over emphasis on physical impairments over psychological impairments.

Hopefully this section provides some insight into which patients may not be appropriate for, or benefit from the pilates approach, and when caution should be taken. It also highlights that self-reflection on our own teaching methods and monitoring of patient participation may reduce the risk of increased pain or aggravation.

What defines pilates exercise and differentiates it from other forms of exercise?

The Pilates method was developed by Joseph Pilates over many years, starting in the early 1900's around the first world war. In 1980 his work was published and brought to the world in the book "The Pilates Method of Physical and Mental Conditioning".

There are three main forms of pilates exercises: repertory, modern, and clinical pilates. The form most applicable to physiotherapists is the latter. These methods have significantly developed over the last 20 years and are used worldwide in rehabilitation.

With the changes that have occurred to improve this exercise method and make it more applicable to rehabilitation for back pain and other injuries, we have lost a strong definition of clinical pilates. There are many themes and identifying features thought to be apart of clinical pilates, which Wells and colleagues investigated further (2013).

There was strong agreement that pilates exercise involves body awareness, breathing control, control of movement, patient education, individualised programs, postural control, patient mindfulness and a measured treatment approach (Wells et al, 2013). There was less consensus that the identifying features of pilates include: concentration, coordination, core stability, direction preference, endurance, flexibility, goal orientated, graded, low impacted, mind-body connection, muscle balance, precision of technique, proprioception etc., but many therapists still considered them as key components and identifying features.

One important point to note from this study is that "consensus was not reached in regard to the prescription of a set number of exercises and the incorporation of rest and cool-down exercise" (Wells et al, 2013, p. 6).

There was strong agreement that essential components may include: functional integration of pilates principles, encouragement, feedback, home exercises, client self-correction, and therapist reassessment. There is less agreement however on whether balance, activation of stabilising muscles, education, equipment, low load, high repetition, pelvic floor screening, and training principles of power, endurance, strength etc are essential components.

Consensus was reached that both the pilates reformer and mirrors were essential pieces of equipment to provide visual feedback, assist with posture, make exercises more comfortable and improve variation of exercises.

And the article continues to explore equipment use, class design, teaching methods and more. There are too many components to cover in this blog so I'll refer you to the original article.

The authors conclude with the following statement. Many "items that did not reach consensus related to identifying features of Pilates, essential components of pilates, essential forms of equipment and rational for use, and exercise prescription principles" (Wells et al, 2013, p. 8). This might explain the large amount of variability in how we teach pilates exercise and apply these principles to the management of patients with chronic lower back pain.

How can this change our clinical practice?

I have completed Level 1 and 2 Clinical pilates training with Dance Medicine Australia (DMA) and teach around 10 hours a week of clinical pilates.

DMA state in their course manual "So, in this course we teach you about Pilates. It is not the "be-all and end-all" of exercise. It is a useful and effective technique to develop the musculo-skeletal system of the human body, nothing more and nothing less. As physiotherapists it is one more tool in your armoury to be used in conjunction with all other techniques and philosophies. Clinical, post graduate experience will tell you when it is appropriate and when it is not. Learn the techniques, perfect your ability to teach them and stay in touch with the research. Be prepared to be challenged on a regular basis as nothing is set in stone or dogma." (Level 1 manual, 2012, p. 4).

Here are some points to consider from:

- The patient population of interest in these studies are people with lower back pain.

- Physiotherapists agreed to the definition that pilates is an umbrella term which encompasses an "individually tailored, graded, supervised, functionally relevant and goal-driven rehabilitation program" (Wells et al, 2014, p. 810).

- Clinical pilates is not a substitute for a multidisciplinary chronic pain program.

- Psychosocial barriers to recovery which require psychology/counselling/psychiatry input and are not likely to achieve the best benefits of pilates if these issues aren't adequately addressed.

- There is a lack on consensus as to the identifying features and many other components of pilates but assessment is crucial.

- There are no strict guidelines for which this approach should be used.

Conclusion.

These articles have reminded me to stop and question if patients are truly suitable and likely to benefit from this approach and also given me confidence to know when it is not likely to be beneficial and may in fact expose my patients to risk of injury or failure for improvement.

After reading these articles I developed a sense of both freedom and deeper understanding that we cannot be constrained by one single treatment method or philosophy. No two patients are the same and each demands us as physiotherapists to be thorough in our assessment and imaginative in our treatment. The primary reason people come under our care is for us to help them with their problem. Whilst the research remains debatable we can focus our attention to the problem in front of us, helping our patients. That may require us to think outside of the square, adapt treatment approaches and merge different philosophies.

"A person who never made a mistake never tried anything new." (Albert Einstein)

Sian

References:

Wells, C., Kolt, G. S., Marshall, P., & Bialocerkowski, A. (2014). Indications, Benefits, and Risks of Pilates Exercise for People With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Delphi Survey of Pilates-Trained Physical Therapists. Physical therapy.

Wells, C., Kolt, G. S., Marshall, P., & Bialocerkowski, A. (2013). The Definition and Application of Pilates Exercise to Treat People With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Delphi Survey of Australian Physical Therapists. Physical therapy.