A neurodynamic approach for posterior shoulder pain

A clinical example

A 60 year old male presents with a two month history of insidious onset left posterior shoulder and arm pain. His symptoms are described as aching and throbbing pain which is worse when sleeping on the left side and during the day with most reaching tasks. He had received five physiotherapy treatments focusing on his neck, thoracic spine and shoulder joint mobilisation. There had been in-session improvement in pain with reaching and joint range of movement, but no between-session carry over.

He was referred for a second opinion on the suspicion that his pain might have a neurodynamic involvement (based on the lack of carry over of treatment effect). Below is an abbreviated list of my assessment.

- At rest the patient reported pain in the distribution seen on this picture.

- His left cervical rotation and lateral flexion was hypomobile, but painfree and didn't change the shoulder pain.

- Shoulder range of movement was painful with reaching forward and across the body, however no passive restriction was found on assessment.

- Upper limb neurological examination was unremarkable.

- Upper limb neurodynamics assessment (median, ulnar and radial nerve) displayed normal responses.

- There was focal tenderness on palpation of the first rib and an increase in shoulder pain.

- It should be noted that thorough examination of the shoulder, cervical and thoracic spine were completed prior to referral.

Interpretation of physical examination and planning of treatment.

So I had found a comparable palpation finding over the first rib. My first thought was to assess the response to mobilisation of the first rib.... but it was too painful. So I thought "how can I offload this patient around the first rib?" And this is what I tried....

I positioned his left arm in the functional position of aggravation i.e I lifted it into flexion and slight horizontal flexion, which decreased the severity of pain. But I couldn't hold it while re-palpating the rib so I got the patient to place his hand on his forehead and rest his arm in the air.

In this position I was able to palpate the first rib. The same response was noted i.e. reproduction/intensification of shoulder pain with a downward glide. It was more tolerable for the patient but still too tender to mobilise.

At this time I needed to offload the tissues further. Based on previous cervical lateral flexion mobilisations, I wanted to assess a different structural differentiation. So I explored the affect of an ipsilateral straight leg raise, which is thought to create convergence of neural tissues back towards the spinal canal. Nerves converge towards the joint which is being moved, in this case the hip. The result of this was a complete reduction of shoulder pain.

This is defined as an overt positive response but not from a standard test. It was a level 1c i.e Position in a degree of tension and move out of tension with the opposite limb (or in this example the lower limb).

This is a positive neurodynamic response.

My interpretation of this response was that neural tissue displayed mechanosensitivity as they passed underneath the clavicle and over the first rib. Many people consider this region to lead to thoracic outlet syndrome. In this case however, it was resulting in shoulder pain.

So my next thought was "If I can't mobilise the rib, then how can I improve the mobility around this region through a neuro-centric approach?" The aim of treatment was pain reduction through reduction in nerve mechanosensitivity by mobilising the surrounding interface.

The patient continued to hold their arm in the air with their hand on their head. I encouraged the patient to breathe comfortably and diaphragmatically (to encourage a downward rib movement away from the clavicle on expiration) and I performed a repeated straight leg raise for 30 seconds.

Very quickly his symptoms resolved and on reassessment, palpation of the first rib was tolerable.

As a treatment progressed I was able to mobilise his first rib with a downward glide on expiration and slowly place the patient's hand down on the bed.

His response was very quick and all these treatments occurred as a sequence of treatment progressions within one session. It isn't generally recommended that one progresses/changes that many times within one session, but in this case specifically, he wasn't irritable or in severe pain and happy to continue with the progression.

Following the treatment his functional aggravating movements were pain-free.

As a home exercise program I encouraged diaphragmatic breathing and self sustained holds over the first rib in an offloaded position.

How do you explain this to a patient who presents with shoulder pain and the treatment of choice is to raise their leg into the air? Well... he just laughed when I asked about any change in symptoms and he replied "My shoulder pain has completely gone. What did you do?"

What did I do? I varied away from the standard neurodynamic test. I used the tools from Michael's course to vary the degree of assessment and treatment. I used my new knowledge of convergence and tension dysfunctions to place the patient in a position more suitable for treatment.

From, Shacklock M, Clinical Neurodynamics, Elsevier, Oxford, 2005.

Ten key messages from the Neurodynamic Solutions Course

- During assessment, if you can exclude neurodynamics as a problem it will make the clinical reasoning process clearer.

- Know where to start and when to stop.

- Neurodynamics does not mean neural tension.

- In 96% of healthy individuals there will be a change in symptoms with structural differentiation. This is not considered a false positive test result. It is about how we interpret the positive result to determine if it is a overt or covert response and if it relates to the problem.

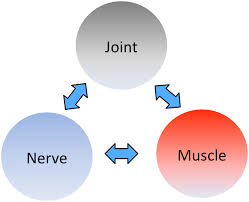

- There are three ways to move a nerve: move the joint it crosses, move the tissue it innervates, or move the interface surrounding it.

- Nerves move in many ways: longitudinal and transverse sliding, elongation, bending and convergence. The nerve will converge (i.e. move towards) towards the joint at which the movement is occurring.

- Structural differentiation is involved in every neurodynamic test and involves movement of a body part away from the area being assessed to evaluate the effect of mechanical force on the nervous system and its impact on the problem/pain.

- Using structural differentiation we can safely sequence movements from protective movements to sliders then to tensioners and through to focused movements.

- Nerve palpation is a helpful way to differentiate peripheral from central changes in the nervous system as it gives us information about allodynia and hypersensitivity (generalised vs. specific). Central sensitisation pain will tend to be more generalised while peripheral sensitisation will result in pain in the surrounding tissues only.

- Don't tell patients you are assessing their neural tissues because it can change the outcome of the tests through their beliefs. Have a prepared statement which may sound like this "I am going to perform a movement and see how you respond. You may or may not feeling anything. During the test I want you to tell me if you feel anything and where you feel but do not move to show me. At some point during the test I may ask you to move your head towards or away from me like this (show them side-flexion). Are you happy for me to continue?"

And that is a small preview of all you can learn about this approach through Neurodynamic Solutions. I hope you found this helpful and that it has demonstrated how one can vary assessment and treatment to suit the patient while still maintaining a neurodynamic approach.

For further information I would refer you to Shacklock's text book Clinical Neurodynamics.

References:

Shacklock, M. (1995). Neurodynamics. Physiotherapy, 81(1), 9-16.

Shacklock, M. O. (2005). Clinical neurodynamics: a new system of musculoskeletal treatment. Elsevier Health Sciences.